January 16, 2023

My Rickman report has finally turned into my BSA report. After slightly over a year delay from my original plans, my son Eric and I have finally started on the teardown and rebuilding of my 1964 BSA Spitfire Hornet. This was my first motorcycle, which I bought in 1965. In a couple of words, it was destroyed when I bought it, having been raced to death, taken apart, placed in boxes, and then sold as is. Being naïve but energetic, I thought it would be a great project and when finished I would have a cool British 650cc bike.

In the early and mid 1960’s British bikes were the bikes to own. They were powerful, looked and sounded cool and especially fun to ride with great handling. Their reign didn’t last too long as the Japanese and later the Italians came out with MUCH more powerful and refined machines, dooming the British bike industry by the early to mid 1970’s. BSA was the largest motorcycle manufacturer in the world in the early 1960’s and 10-12 years later they were no more. BSA owned Triumph too, which lasted into the mid 1970’s, but their corporate culture doomed them once the Japanese arrived with Honda’s, Yamaha’s, Suzuki’s and Kawasaki’s. Arguably, the Honda 750 four was the final nail in the British coffin, but the British had one foot in the grave when Honda’s 250 scrambler first appeared. The factory thought it “knew it all”, but in fact, knew little. The running joke was, 100 years of tradition uninterrupted by technology. Triumph came back in the 1990’s as a different company still located in England, and recently the rights were sold for the name of a couple of British bikes and have resulted in a few new models (Royal Enfield and BSA Goldstar), but they aren’t made in England and are total remakes.

The Japanese did what the British refused to do, both in motorcycles and cars. They innovated and refined. They had electric starting. In fact their entire electric systems worked. They didn’t leak oil out of every seam possible and were well engineered so the average person could just ride and not have to continually tinker and repair one’s machine. Japanese bikes actually idled smoothly and went untouched for miles and miles.

But for many, especially those with mechanical skills, there was nothing like a British machine. They handled extremely well, were fun to ride, powerful for their day and in the right hands, were “fairly” reliable. For me, I loved the challenge of trying to make a road oiling BSA into something better than the factory could ever do. I wasn’t alone as over the years encountered many others who felt the same way. We all wondered how such a good basic design could be engineered and constructed so poorly when the competition seemed to get it correct, right out of the box.

In 1963, although few were sold in the US, BSA had changed their 650cc model from an engine and separate transmission, to a unit construction motor, which also housed the transmission (Triumph did the same). They introduced the A-50, 500cc models, and the A-65, 650cc bikes. These new engines replaced the A-7 and A-10 pre-unit models. They were a little lighter and a little more powerful, but I suspect it was cost savings that drove them towards unit construction. The A-65, like the A-10 before it is a 2-cylinder vertical twin, overhead valve engine. The basic engine wasn’t too bad, and in my opinion, if one modified or removed the Lucas electric system and replaced the Amal carburetors, one was on their way to a better machine both from a reliability and performance standpoint.

I knew none of this at first however. The basket case I bought happened to be one of the first unit BSA’s and very close to one of the first Spitfire Hornets, BSA’s racing model introduced in 1964. At the time, Cycle World claimed it did 120MPH in their road test, and Wikipedia says that Motor Cycle, a British Magazine, claims a top speed of 123MPH with a 2-way average of 119.2 MPH for the 1966 model. Maybe. The Spitfire Hornet competed with Triumph’s TT Special. They both came from the factory with high compression pistons and a hotter cam(s) than the BSA Lighting or the Triumph Bonneville, their road versions 650cc bikes. Both had straight exhaust pipes with no silencers. My engine number is A65E342. BSA started their unit numbering at 100, which included all models, so this BSA is a very early example of a unit Spitfire Hornet. It needed lots of work because of its previous owner. The frame was broken, needed welding, and many of the parts were shot. The fiberglass gas tank was also cracked and leaking. In a few weeks I had repaired it, got it running and just loved the bike. It still had many problems. It wouldn’t stay in most gears (thanks to the previous owner who beat the crap out of it), so almost from the start I started repairing and modifying it. I purchased all new gears and shifting forks and solved the shifting issues. I rode the bike daily while I was in college and with friends on the weekends.

The BSA Spitfire Hornet and the Triumph TT Special didn’t come with lights or a battery but instead ran directly off the 6-volt alternator. Lights could be added which I did, but even at higher revs they were so dim that above 40 MPH or so on a dark curvy country road you just rand out of headlight. When the bike stopped running you were in total darkness. The Lucas alternator was also undependable and broke on me at least 2 times leaving me stranded on a back county road in total darkness on one of those occasions. Lucas eventually made an epoxy encapsulated alternator which was somewhat more dependable, but that wasn’t until around 1967. Lucas electric parts were a continual issue and the bike constantly had to be timed since the points plate was flimsily. Keeping it in top performance mode took constant tinkering.

My personal wakeup call about Japanese motorcycles came on Sunset Blvd. at a stoplight when a guy on a 450 Honda came up along side of me. The light turned green and we both took off hard. I was sure that with 200 more cc’s that I would smoke him, but the opposite happened. We repeated this at the next light and he was gone. I decided there that modifications were needed! I purchased some Devimead (now SRM) 750cc barrels and pistons, junked the Lucas points that would NOT stay in time, machined a new point plate using Yamaha points, and dumped the 30mm Amal carburetors for a pair of 34mm Mukuni’s. This along with a 2 into 1 Kerker exhaust brought this bike to life. I never found the guy on the 450 Honda but I was always looking!

In 1968 I got a job working at Kosman Specialties, at 340 Fell St. in San Francisco. This was a real eye opener for me. Sandy Kosman was at the top of the heap in the motorcycling racing world then and throughout his entire life. I worked on everything and learned a ton. Kosman was most known in the drag racing world, but also with flat track racers. Many of the big names in racing came through his shop, including Dick Mann, Mert Lawwill, Carl Rhodes, Alf Hagon, and many others. I also learned that my modified BSA could be built into another level after working on some of the machines at his shop. One such bike was the engine that is now in the Rickman Triumph I now own. It was originally built by Carl Rhodes as a 650cc and in a drag bike frame it clocked over 120 MPH in the standing ¼ mile in just over 11 seconds. When I first rode the Rickman in 1970, now an 800cc motor, I knew that the British bike industry had missed the boat.

Late 1971 when I left Kosman I had many other things going in my life and the only changes to my BSA were an alloy oil tank, oil cooler, Ceriani Forks, an oil filter etc. I rode on the weekends only by then with my friend Bill Truscott who ended up buying the Rickman Triumph I now own. Bill started an auto parts distrubition company, which, consumed all his time, and by the mid to late 70’s we hardly rode. Bill died at age 49 in 1979 and the last registration on my BSA is from 1982. Although I would kick over the engine now and then, its been sitting in the same spot in the back of my garage since 1982.

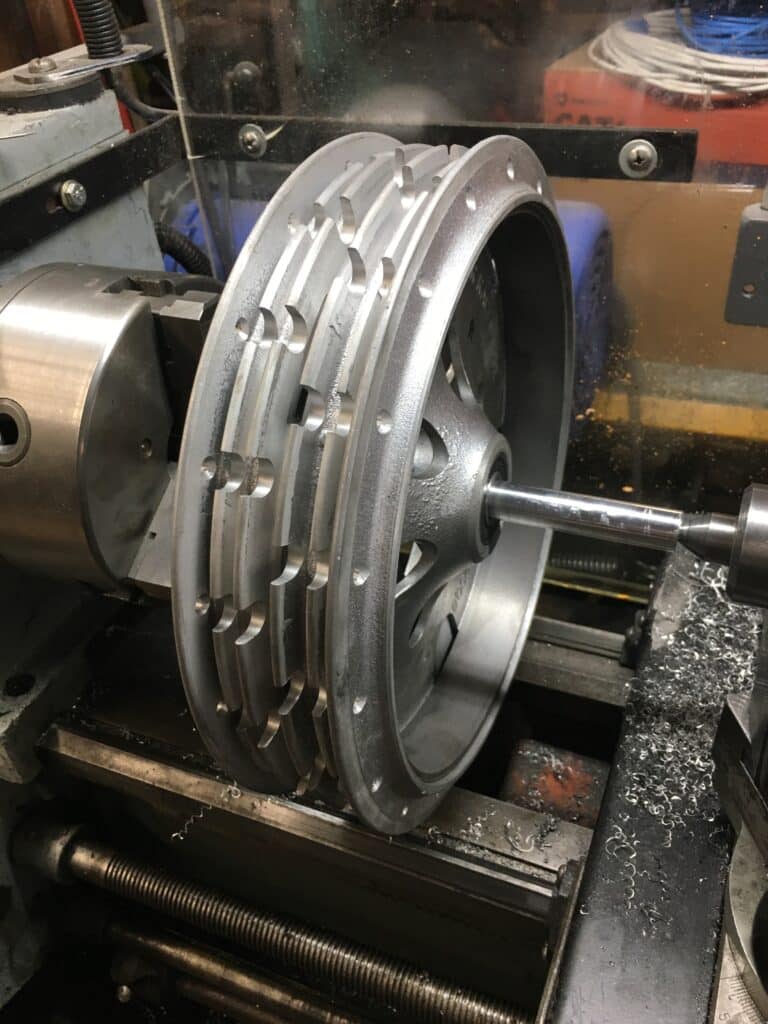

When I finished restoring the Rickman, I new I wanted to start on the BSA. My plan was to strip the bike, make the modifications to the frame, brakes, and suspension, and complete a rolling chassis that would be ready for a highly modified motor. The single leading shoe front brake started to become useless after about 40 MPH, even though the 8” brake was raved about in 1964. Times change. About 6 months ago I bought a 230mm Robinson 4 leading shoe (4LS) road racing front brake (from The Czech Republic), a Boranni 19” rim (from Italy), and Buchannan stainless steel spokes (USA), which arrived in a week once I knew the spoke circle diameter of the brake. It took over 3 months for the brake to show up and over a month for the rim, which I needed in order to size the spokes. I didn’t want to order spokes until I had the brake and rim in my hands. I polished the SS spokes, turned the brake hub in my lathe to remove crude castings, had the entire brake vapor blasted and then I laced and trued the front wheel. I realize the worst disc front brake is most likely better than even this large 4LS front brake, but we are trying to keep the bike period correct where we can, and large 4LS brakes look so cool and still work fairly well.

The tires on this bike are Dunlap K-70’S that look like new, but are over 50 years old. They have hardened over this amount of time and most likely aren’t safe so they are history. The K-70’s on the Rickman are the same age and on my last ride in the fall, they didn’t have lots of traction, as the rubber is hard. They will be going too. This started another saga of finding vintage tires, K-70’s are still available, BUT they have a speed rating of 112 MPH. When new and running right, a BSA Hornet did that or a little more. Another vintage tire I really like the look of, even better than the K-70 is the Duro HF308. However, its speed rating is only 93 MPH. Several British bikes were capable of close to 120 MPH in the 1960’s and I decided these tires were out for me. Eric and I plan to highly modify this engine and although it won’t be me on the bike anywhere near its potential, I don’t want an underperforming tire. We have decided on Avon Road Rider Mk 2 tires that DON’T have a vintage look, but do have a speed rating of 149MPH. Avon also make tires sized for British bikes. This bike could be capable of 130 plus MPH when we complete it. I justify this in the same way an electrician would when putting in a new electrical service. A 200-amp service requires 2/0 size copper wire and just because the homeowner may never use all 200 amps, the wire must be that size for safety if they did need all 200 amps.

Unfortunately, due to supply chain issues, the front Avon tire is on back-order with no ship date. So I have a wheel and brake waiting for a tire, and a Ceriani road race front end all polished waiting for the wheel. A few days ago, about a year later than I had planned, we tore down the BSA, removed the old motocross Ceriani front end and stock BSA wheel and brake. Something I was sure I did over fifty years ago was to replace the individual ball bearings in the headset with Timken tapered roller bearings. I must have a bad memory because upon removing the front end 60 or 80 ball bearings hit the floor and went everywhere. We scooped up as many as we saw and I just ordered the Timken bearings for the headset. The bearings arrive mid next week and we will cut the stem slightly for them to fit and make spacers for the frame head tube.

The other thing I discovered (so far) is how crude some of my work was over 55 years ago compared to what I will do now. I will fix or replace all the cheesy brackets and parts I made with more sophisticated parts. We plan to weld gussets and stiffen the frame where needed and the swing arm will get a truss modification to improve stiffness and handling. We debated building a new stiff swing arm, but the period look, even modified with a truss is our choice. Eric and I are stoked about this project and we have big plans for the motor, once we have a finished rolling chassis. We plan to machine the timing side crank bearing to fit a roller bearing with end feed oiling, in place of the bushing bearing. We also plan to cut the crank in half and index it 90 degrees so it wont be a parallel twin any longer and have MUCH less vibration than a stock British twin. This will involve a new 90-degree cam grind and ignition. Along with head modifications and porting, larger valves and various other tweaks will keep us busy. I’ll discuss the engines strengths and weaknesses in another chapter. We are finally on the move!

Great story update👍

Fantastic article, loved the tech info and the history lesson! Keep up the good work! I’m currently building my wife’s 47 Triumph T100, lots of custom bits due to its vintage and previous life! Cheers!

Thanks for the encouragement!! Good luck on your project. /Larry